First Trust Monday Morning Outlook

Brian S. Wesbury - Chief Economist

Robert Stein, CFA - Dep. Chief Economist

June 24, 2024

Back in the early days of COVID, there was one key indicator that signaled or predicted the high inflation ahead: the M2 measure of the money supply. Unlike in the aftermath of the Financial Panic and Great Recession of 2008-09, M2 surged at an unprecedented pace in 2020-21.

So, while others looked back and said “QE doesn’t cause inflation” we didn’t. While many said that inflation was “transitory,” we warned about inflation going higher and being more persistent. And here we are more than four years past the onset of COVID and inflation is still lingering above the preCOVID trend. The Consumer Price index is up 3.3% from a year ago while core consumer prices are up 3.4%.

What we take from all of this is that many economists, investors and policymakers ignored M2 to their detriment. As a result, they have been surprised by the surge and persistence of inflation. You think they might have learned.

But now a new conventional wisdom has taken hold, which says the US is out of the woods on a potential recession. This, in their view, supports a trailing price-to-earnings ratio of 24 on the S&P 500, a level that in the past has been associated with low future returns on equities.

We hope a recession doesn’t happen, but think their dismissive attitudes towards warning signs like M2 (which has declined in the past 18 months) increases the chances they get caught flat-footed by a downturn. We know it’s not visible yet, but every once-in-a-while there’s an economic report that should make people re-think their pre-conceived notions.

That applies to home building in May. Out of the blue, housing starts dropped 5.5%, completions fell 8.4%, and permits for future construction declined 3.8%.

Housing starts and permits are now sitting at the lowest levels since the early days of COVID, even as the flow of immigration remains elevated. Whether you support or oppose high levels of immigration, where are all the newcomers going to live if we aren’t building more housing? And isn’t one of the arguments in support of high immigration that industries like home construction need cheap labor to build more homes?

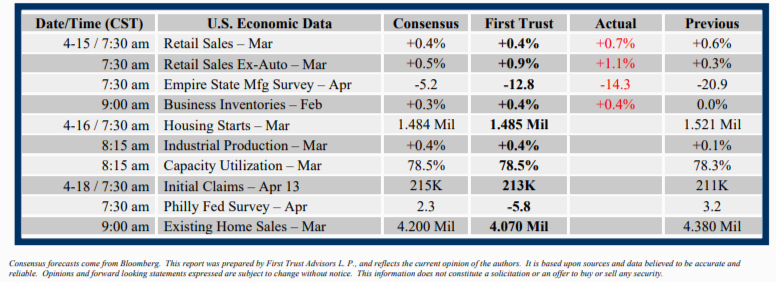

In the meantime, retail sales surprised to the downside in May, eking out only a 0.1% gain for the month, but including revisions to prior months were actually 0.3% lower. Retail activity is roughly unchanged since the end of last year, which means after adjusting for inflation, consumers are buying fewer goods. Car sales rose slightly in May, but are down from last December and even down from June 2023.

In addition there’s an early sign that the labor market may have some trouble ahead: initial claims for unemployment insurance averaged 211,000 per week in the fourth quarter of 2023, as well as the first quarter of 2024. But initial claims have averaged about 240,000 in the past two weeks. Hopefully this is just some seasonal variation and claims will go back down soon, but it is worth watching closely in the weeks ahead. (One caveat is Thursday’s initial claims report will include Juneteenth, a relatively new holiday which may confuse seasonal adjustments.)

None of this means a recession has already started. Industrial production surged 0.9% in May, which is not a recessionary number at all. The Atlanta Fed GDP Model is back up to tracking 3.0% annualized growth in Q2, while we are tracking 2.0%. And private payrolls continue to average over 200,000 jobs added per month, even if gains appear to have been led by part-time positions.

It's also important to recognize that fiscal policy has never been this “loose” (the deficit so high) when the unemployment rate has been so low. But with the interest burden on the federal debt as a share of GDP suddenly shooting up to the highest since the 1980-90s, the days of using the budget to try to artificially boost growth should soon come to an end.

There’s no guarantee of a recession in the year ahead, but the risk shouldn’t be casually dismissed. Not paying attention to M2 has cost investors more than once already.

The attached information was developed by First Trust, an independent third party. The opinions are of the listed authors at First Trust Advisors L.P, and are independent from and not necessarily those of RJFS or Raymond James. All investments are subject to risk. There is no guarantee that these statements, opinions, or forecasts provided in the attached article will prove to be correct. Individual investor's results will vary. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Forward looking data is subject to change at any time and there is no assurance that projections will be realized. Any information provided is for informational purposes only and does not constitute a recommendation. Investing involves risk and you may incur a profit or loss regardless of strategy selected.