First Trust Monday Morning Outlook

Brian S. Wesbury - Chief Economist

Robert Stein, CFA - Dep. Chief Economist

March 11, 2024

If you only look at the headlines about the monthly payroll report, the job market has looked surprisingly strong in recent months. Nonfarm payrolls rose 275,000 in February, beating the consensus expected 200,000 as well as the average of 229,000 per month in the past year.

But a deeper look at the data makes it look about as fishy as week-old sushi. Now, we’re not alleging some sort of “Deep State” conspiracy, we’ll leave that to others. But reviewing the report in its entirety show the job market is not nearly as strong as the top line payroll readings suggest.

For example, look at the revisions. Payrolls in December and January were revised down by a total of 167,000 (the largest monthly downgrade for any non-shutdown months since late 2008), meaning February was just 108,000 above the original January level. And it was even worse in the private sector, where payroll gains were a paltry 19,000 for the month after netting out revisions for prior months.

What’s odd about these downward revisions is that they seem to happen pretty darn often of late. In 2023, for example, the regular two-month revision process reduced the initial monthly report by 30,000, on average. That ain’t chump change. In the past few decades, negative revisions like this have normally been associated with recessions or the immediate aftermath of recessions.

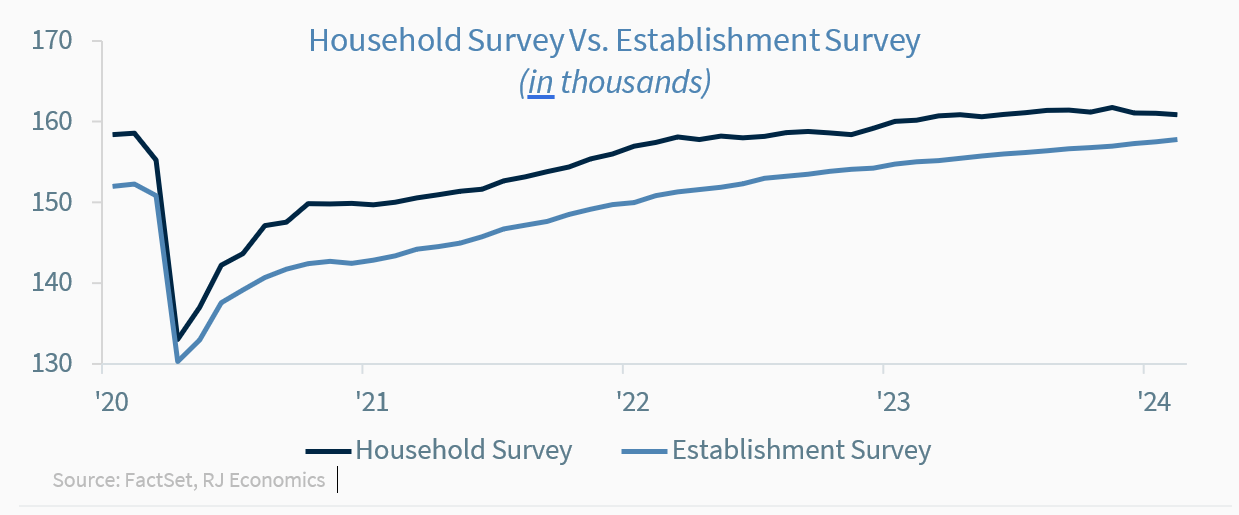

It's also important to follow civilian employment, an alternative measure of jobs that includes small-business start-ups. On a monthly basis, these figures are volatile, and are affected by estimates of the size of the total population, so take them with a grain of salt. But the trend is important and isn’t anywhere as strong as payrolls. While payrolls are up 2.7 million in the past year, civilian employment is up 0.7 million and the unemployment rate has risen to 3.9%. Moreover, the gain in civilian employment in the past year has all come in part-time work, with a slight loss for full-time jobs.

There may be solid technical reasons for this large gap. The figures are generated by two different surveys (one for employers, the other for households), and maybe the massive influx in immigrants, even if largely illegal, is finding its way into payroll expansion (perhaps with illegal hiring or false documents) in a way not being picked up by the civilian survey. We’re guessing many recent immigrants are not eager to answer surveys sent by the Labor Department.

Notably, among those who do answer the survey, civilian employment among the native-born population is down around 900,000 from a year ago – the first drop since the onset of COVID – versus an increase of about 1.5 million among the foreign-born.

Only time will tell the true underlying health of the labor market. There is no clear signal we’re in a recession, but the patient isn’t looking well. What is clear, is that economic risks abound, and a soft landing is far from guaranteed.

The attached information was developed by First Trust, an independent third party. The opinions are of the listed authors at First Trust Advisors L.P, and are independent from and not necessarily those of RJFS or Raymond James. All investments are subject to risk. There is no guarantee that these statements, opinions, or forecasts provided in the attached article will prove to be correct. Individual investor's results will vary. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Forward looking data is subject to change at any time and there is no assurance that projections will be realized. Any information provided is for informational purposes only and does not constitute a recommendation. Investing involves risk and you may incur a profit or loss regardless of strategy selected.