First Trust Economics

Three on Thursday

Brian S. Wesbury - Chief Economist

March 27, 2025

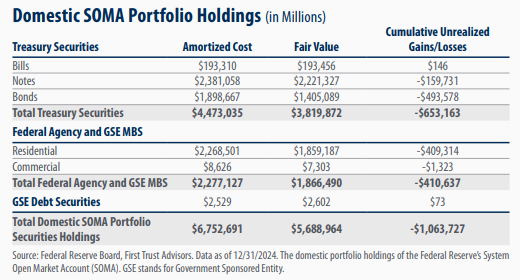

In this week’s edition of “Three on Thursday,” we look at the Federal Reserve’s financials through year-end 2024. Back in 2008, the Federal Reserve (the “Fed”) embarked on a novel experiment in monetary policy by transitioning from a “scarce reserve” system to one characterized by “abundant reserves.” In addition to inflation, this experiment has resulted in some other developments that are worrisome. Higher interest rates have resulted in substantial unrealized losses on the Fed’s securities portfolio. Simultaneously, they have caused the Fed to pay out more in interest to banks than it is earning, resulting in sizable and ongoing losses. To offer deeper insights into where things stood at the end of last year, we have included the two charts and table below.

Before 2022, the Fed was able to buy Treasury and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) that generated higher yields than what they were paying banks. Consequently, the Fed consistently earned substantial operating surpluses, which were then remitted to the Treasury Department on a weekly basis. Over a span of 15 years, the Fed contributed an average of over $75 billion annually to government revenue through this mechanism. But now, even with the 100 basis point reduction in the Fed funds rate last year, it’s still paying banks 4.4% per annum to hold reserves – much more than what it earns from its portfolio of Treasury bonds and MBS. These higher rates have led to $79 billion in losses over 2024. These accumulated losses are called a deferred asset on the Fed’s balance sheet and will only be paid off if/when the Fed starts to make a profit again down the road. This deferred asset, which represents all accumulated losses so far, stood at $216 billion at the end of 2024.

At the end of 2024, the Fed had a $1.06 trillion unrealized loss on its balance sheet, but it’s important to note the unique position it’s in. Unlike many financial institutions, the Fed doesn’t face solvency concerns because it’s not required to mark its portfolio to market values. The Fed has the option to hold its securities until they mature, and there’s no regulatory agency that can intervene and force it to shut down due to accounting losses. With total reported capital of just $44 billion at the end of 2024, the Fed’s unrealized loss of $1.06 trillion represents a staggering 24 times its capital.

In 2024, the Fed compensated banks and financial institutions a total of $227 billion in interest for holding reserves, down from the $281 billion paid out in risk-free income in 2023—a sum that ultimately is borne by taxpayers. Market analysts and the Federal Reserve anticipate a reduction in the Fed funds rate by a total of 50 basis points through two cuts in 2025. This adjustment, coupled with a reduction in the Fed’s balance sheet throughout the year, is expected to decrease the Fed’s expenditure on interest payments to banks and financial institutions as happened in 2024. However, the projected expenses remain remarkably high, we estimate to be between $150 billion and $200 billion, indicating a continuation of significant payouts in 2025.

The attached information was developed by First Trust, an independent third party. The opinions are of the listed authors at First Trust Advisors L.P, and are independent from and not necessarily those of RJFS or Raymond James. All investments are subject to risk. There is no guarantee that these statements, opinions, or forecasts provided in the attached article will prove to be correct. Individual investor's results will vary. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Forward looking data is subject to change at any time and there is no assurance that projections will be realized. Any information provided is for informational purposes only and does not constitute a recommendation. Investing involves risk and you may incur a profit or loss regardless of strategy selected.