First Trust – MMO

Brian S. Wesbury – Chief Economist

Robert Stein, CFA – Dep. Chief Economist

Strider Elass – Senior Economist

Andrew Opdyke, CFA – Senior Economist

Bryce Gill – Economist

With less than three months left before the 2022 midterm elections, it is officially silly season when it comes to interpreting economic reports. For many analysts it’s pretty much all politics all the time, with data seen through a political lens first, and with real unbiased economic analysis coming maybe second, if ever.

It started off with those saying we’re in a recession because, at least based on the most recent reports, real GDP declined in both of the first and second quarters of the year. Never mind that the unemployment rate has dropped 0.4 percentage points so far this year. Never mind that payrolls are up an average of 471,000 per month, while industrial production is up at a 5.2% annual rate over the first six months of the year. Never mind that “real” (inflationadjusted) gross domestic income was up in the first quarter (we’re still waiting for Q2 data) and has just as good of a track record as real GDP.

Ultimately, those claiming a recession started already wanted to score political points against the President and no other reports besides GDP would stand between them and that goal. Our view is that a recession is coming, that monetary policy will have to get unusually tight for the Federal Reserve to bring inflation back down to its 2.0% target. In turn, tighter money should induce a recession. But that takes time and the recession hasn’t started yet.

And now it’s the President and his side of the political aisle who are abusing economic reports for their own political ends. It is entirely true that the consumer price index was unchanged in July, the first month without an increase since May 2020. Fair enough. But to use that to suggest the inflation problem is going away is nonsense on stilts.

Energy prices surged 7.5% in June and then dropped 4.6% in July. That’s it. That’s really all you need to know about inflation in the past two months. As a result, overall consumer prices soared 1.3% in June and then were unchanged in July. But a new trend this doesn’t make. Looking at both June and July, combined, consumer prices rose at an annualized 8.1% rate. That is no different at all than the 8.1% annualized increase in April and May, before the extra surge in energy prices in June then the drop in July.

If you look at the unchanged CPI in July and think the Federal Reserve is nearly done, you’re in for a big surprise. The Fed isn’t close to done. Yes, if you follow consumer prices on a year-ago comparison basis, the inflation rate likely peaked at 9.1% in June. But getting from 9.1% down to the 5 – 6% range by sometime next year is the relatively easy part. Getting from there back down near the Fed’s 2.0% target is the hard part. Rents have been increasing rapidly around the country and we don’t see that ending anytime soon, which will make it very tough for the Fed to reach its stated goal.

You’re also deluding yourself if you think the officially-called “Inflation Reduction Act” is actually going to reduce inflation. Inflation is a monetary phenomenon; the bill isn’t going to have any noticeable impact at all.

The bottom line is that, for now, the economy continues to grow and inflation remains a very serious problem. In the meantime, investors need to set aside their personal political preferences and follow economic reports as they are, not as they want them to be because of the political spin their side gets to put on them.

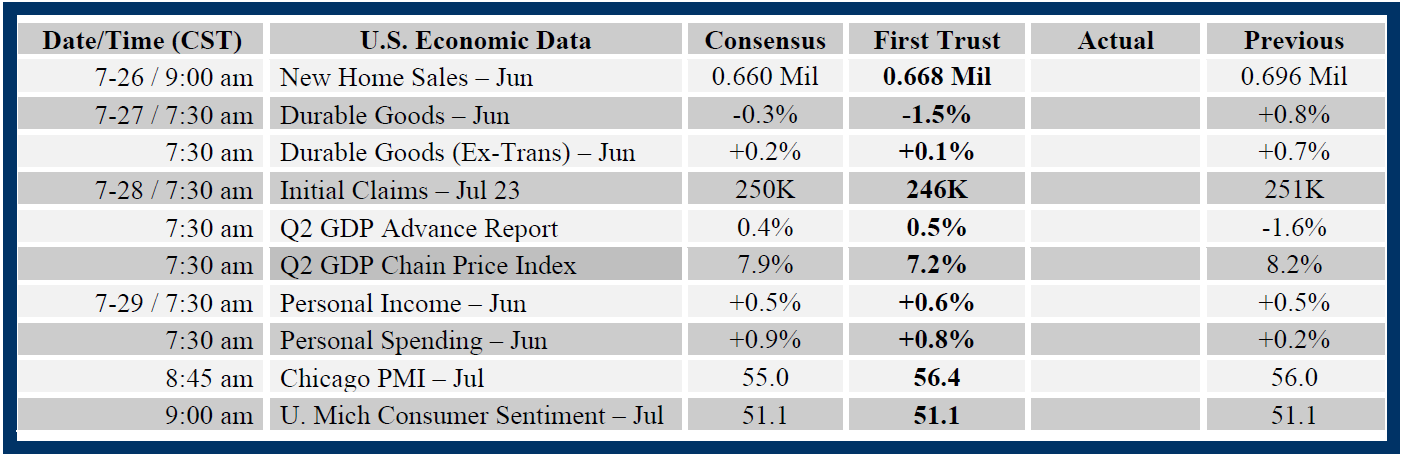

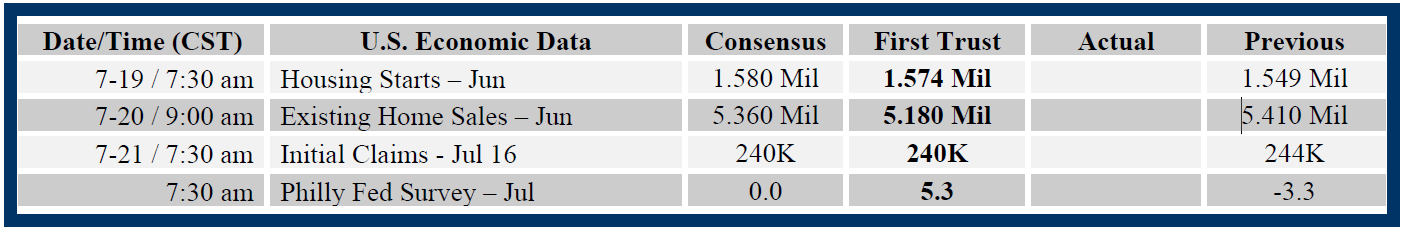

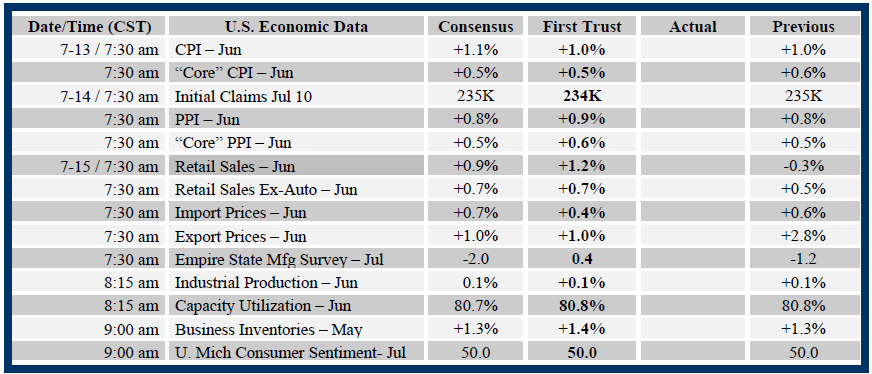

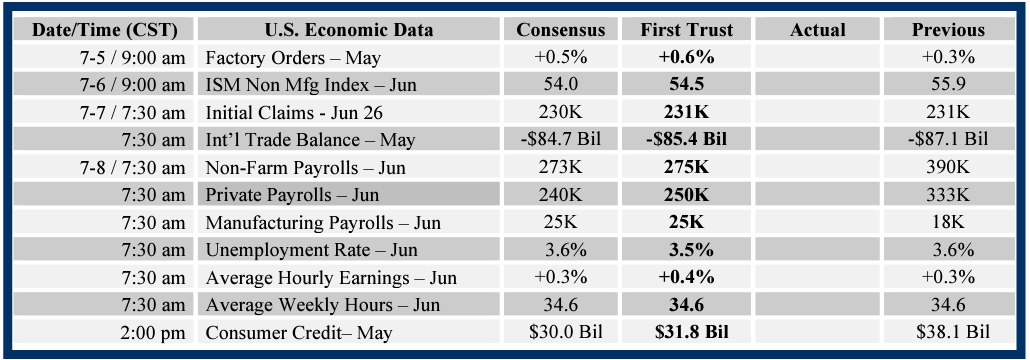

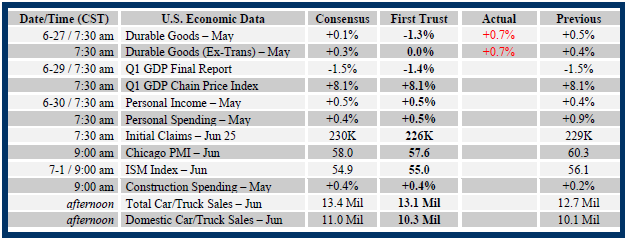

Consensus forecasts come from Bloomberg. This report was prepared by First Trust Advisors L. P., and reflects the current opinion of the authors. It is based upon sources and data believed to be accurate and reliable. Opinions and forward looking statements expressed are subject to change without notice. This information does not constitute a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any security.

The attached information was developed by First Trust, an independent third party. The opinions are of the listed authors at First Trust Advisors L.P, and are independent from and not necessarily those of RJFS or Raymond James. All investments are subject to risk. There is no guarantee that these statements, opinions, or forecasts provided in the attached article will prove to be correct. Individual investor's results will vary. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Forward looking data is subject to change at any time and there is no assurance that projections will be realized. Any information provided is for informational purposes only and does not constitute a recommendation. Investing involves risk and you may incur a profit or loss regardless of strategy selected.